Perk up your ears and listen closely, for the soundtrack of Halloween is creeping up on us: the rustling of candy wrappers, the cracking of chocolate bars, the crunch of hard candies being crushed between eager teeth. This means that it’s time to stock up on not just your neighborhood’s favorite candy, but also some history from our archives—both sweet and sour.

by Alice Levitt

If you’re planning a visit to Malta from the end of October and into November, keep an eye out for għadam tal-mejtin (dead men’s bones), or alternatively, għadam ta’ Novembru (November bones). These bones—which are, spoiler alert, not real bones—are edible memento mori, part of Malta’s longstanding Month of the Dead celebrations. While the outside resembles a large bone-shaped sugar cookie, a bite into the crunchy shell reveals its deliciously warm “marrow” flavored with cardamom and clove.

by Sam O’Brien

In the 19th century, when mourners arrived at somber upper-class Swedish funerals, they could expect to be handed a morsel of ornately-decorated hard candy. The wrapper that enclosed the sweet made no bones about the macabre subject at hand, with designs including skulls, graves, and, in one case, a skeletal figure snipping the strings of time with scissors. Today, the art of creating this funeral confectionery has all but disappeared.

by Jenny Elliott

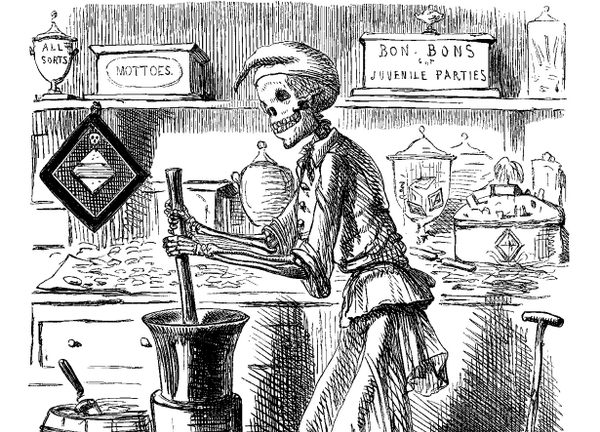

On October 30, 1858, William Hardaker opened his candy stall in Bradford, England, and sold five pounds of striped humbugs—a hard candy flavored with peppermint. By the next day, two children were dead, and by the time the ordeal was over, more had passed, with several hundreds seriously ill. The extra ingredient in the humbugs was arsenic, but it wasn’t inserted maliciously; rather, it was a combination of a shopkeeper assistant’s inexperience, a helping of careless cost-cutting, and the damning lack of safety regulations.

by Vera Armus

What better way to remember a loved one than by sharing some huesos de santo, or saint’s bones, with them? In late October or early November in Spain, bakeries overflow with these vibrant marzipan-based sweets stuffed with a candied egg yolk paste. The bony treats are typically eaten in celebration of the Catholic holidays Día de Todos Los Santos (All Saints’ Day) on November 1, and Día de Los Fieles Difuntos (All Souls’ Day) on November 2. How, exactly, did Spaniards start eating bone-shaped sweets? Now that’s a bit of a mystery.

by Cara Giaimo

In the 1980s, a crime ring dubbed the “Mystery Man with 21 Faces” set in motion a reign of terror by stocking Japan’s supermarkets with cyanide-filled candy, kidnapping candy company executives (who later escaped), publishing threatening letters, and even unsubtly mocking the police. To this day, no one has any idea who they were.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.