When artist Joseph Lindon Smith arrived in Giza a century ago, it was on the heels of an exciting discovery: a tomb chapel for a high-ranking Egyptian official named Idu dating to 2390–2361 B.C.E.

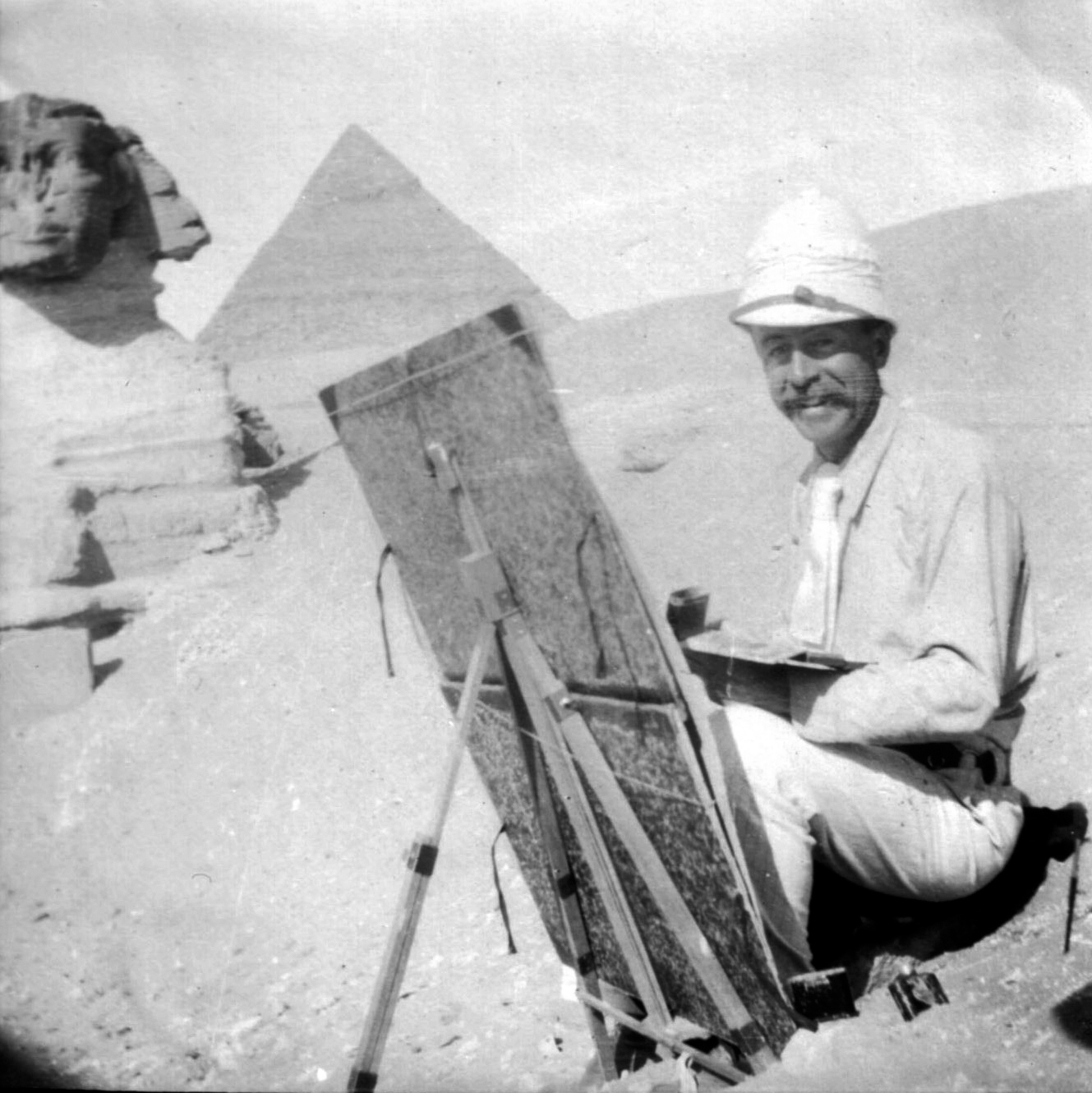

Color photography had not yet advanced enough to be of use to archaeologists in 1925, so the Harvard University-Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition had enlisted Smith, a former portrait artist trained in Boston, to document finds inside the Tomb of Idu. Such brightly colored renderings of archaeological sites remain valuable to scholars today.

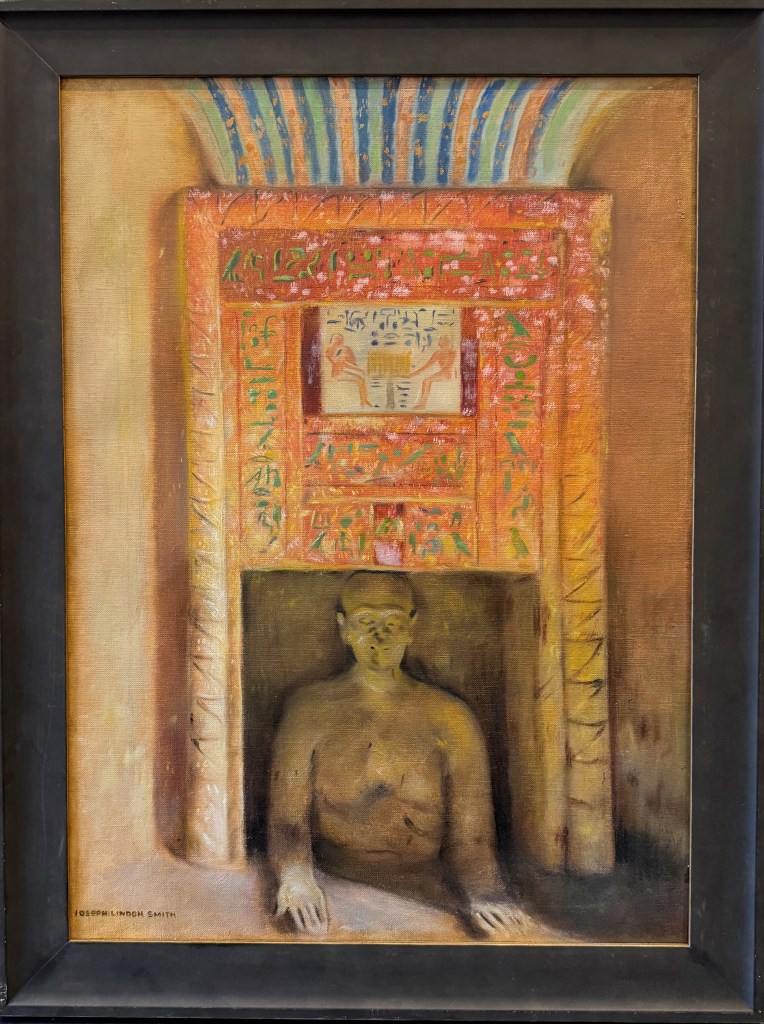

In fact, the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East recently acquired “The Royal Scribe, Idu” — one of the roughly five paintings Smith made over two months at work in the tomb — now on view in a second-floor exhibition.

Peter Der Manuelian.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

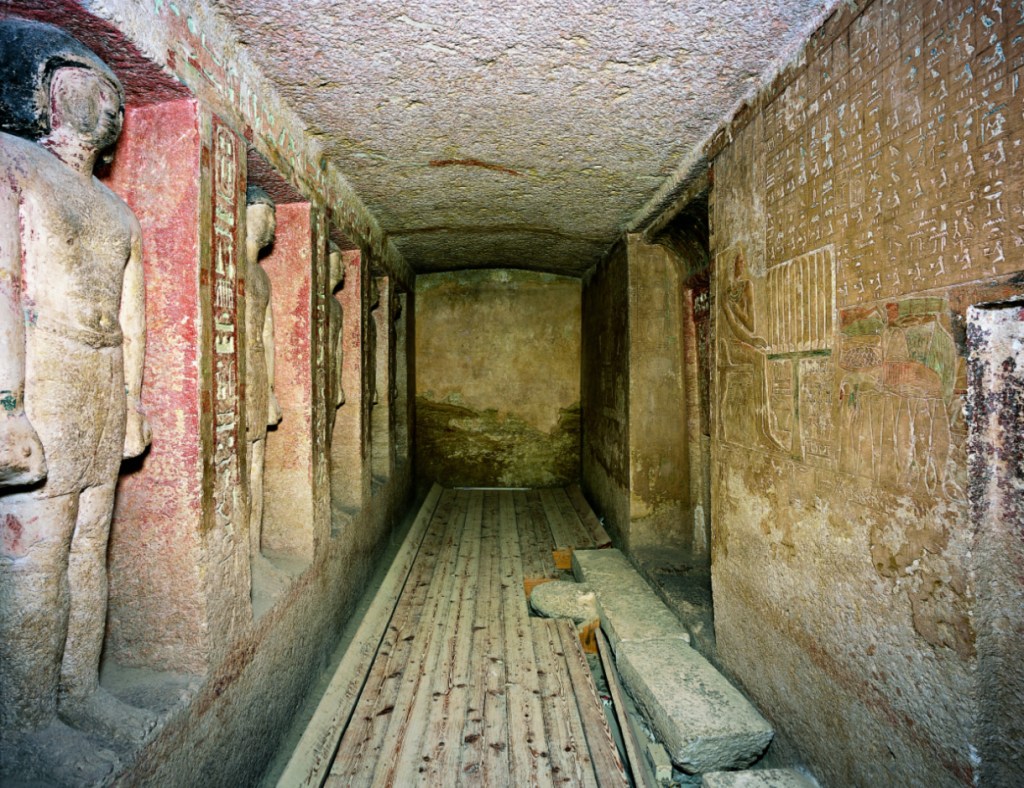

“The monuments are changing. There’s deterioration, there’s the elements; sometimes, unfortunately, there’s mistreatment,” said Peter Der Manuelian, museum director and Barbara Bell Professor of Egyptology. “Any documentation you get from the old days that shows things in a different or better-preserved state than you see them today — maybe with more colors preserved — is always welcome.”

The painting depicts a statue of Idu from the waist up, framed within a decorative “false door” on the tomb chapel’s west wall. Ancient Egyptians would leave food offerings there, believing the souls of the deceased could freely enter and exit from the netherworld. Hieroglyphs above include spells, Idu’s name, and his job titles.

Photo of the statue of Idu emerging from the “false door.”

Courtesy of White Star Publishers

“There are thousands of false doors all over Egypt. What makes this one interesting is this upper torso of Idu himself, the tomb owner, as if he’s coming up out of the netherworld,” Manuelian said. “He’s even got his hands out, saying, ‘I’m ready to take the offerings.’”

In his 1925 diary, Smith wrote about painting the Idu statue, saying “I finished my study of the ‘Bachsheesh’ man and began one of his little son at the left of the doorway.” In Arabic, “baksheesh” refers to money given as a tip, likely a reference to the statue’s outstretched hands, according to Manuelian.

The underground tomb chapel of Idu was uncovered by Harvard-MFA archaeologists in 1925.

Courtesy of White Star Publishers

Scientists today chronicle dig sites using technology such as photogrammetry to make 3D models. But before photography became advanced enough to properly capture color and detail in low-light environments, archaeologists often used line drawings, Manuelian said. It’s no wonder the work of artists like Smith was highly valued by Egyptologist and Harvard Professor George A. Reisner, who directed the Harvard-MFA Expedition from 1905 to 1947 on the Giza Plateau and other sites in Egypt and Sudan.

“Reisner saw them as academically valuable as well as aesthetically beautiful,” Manuelian said. “He loved that Smith could get this three-dimensionality in his two-dimensional paintings and make them visually pleasing, but also a good source of documentation.”

Today the MFA owns more than 100 of Smith’s paintings. The Harvard Art Museums has close to 100 of his works, but only a few of these show ancient Egyptian subjects.

“We are really happy to have this connection to Joseph Lindon Smith at Harvard,” Manuelian said. “It’s an aesthetic piece, it connects to the Harvard-MFA Expedition, and it’s one of Smith’s Egyptian paintings. I think it helps tell that story.”

Source link