For Quantum Computing, Pressing the Advantage Is a Risky Proposition

D-Wave’s fresh claim that it has achieved “quantum advantage” has sparked criticism of the company—and of the scientific process itself

D-Wave, a British Columbia–based technology firm, made a scientific and stock-market splash on Wednesday with its declaration of a breakthrough in quantum computing. But for some experts, the company’s claims are landing with a thud.

What Did D-Wave Do?

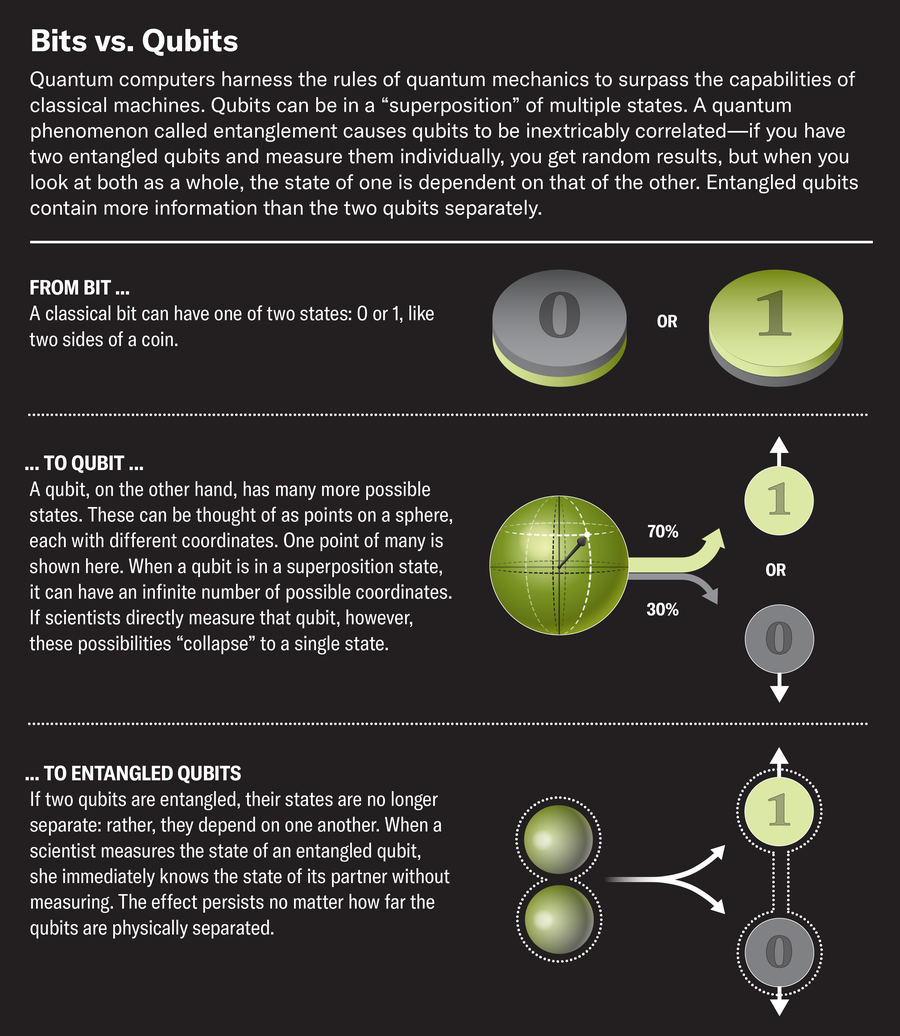

In a paper published in Science, an international team of more than 60 people led by D-Wave scientist Andrew King reported a demonstration of “quantum advantage,” which occurs when a quantum computer solves a problem that would be nigh impossible for a classical computer to handle. Quantum computers derive their number-crunching power from quantum bits, or qubits. Unlike the regular binary bits of classical computers, which use 1’s and 0’s, qubits can use values of 0, 1 and any increment in between. Classical computers handle calculations like an assembly line, bit by bit. Quantum computers can use carefully orchestrated arrays of qubits to simultaneously consider all possible values, exponentially increasing the speed and breadth of calculations.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Using the company’s qubit-packed Advantage2 quantum processor, the D-Wave team accurately simulated how certain physical transitions occur within magnetic materials—a key consideration in manufacturing smartphones and other advanced electronic devices. According to a company press release, the feat shows that the Advantage2 chip “performs magnetic materials simulation in minutes that would take nearly one million years and more than the world’s annual electricity consumption to solve using a classical supercomputer.”

What Happened Next?

D-Wave’s stock price increased by 10 percent in subsequent same-day trading, and the announcement led to strong stock-price gains for several other quantum-computing companies such as Quantum Computing, IonQ, Arqit Quantum and Rigetti Computing. Such upticks are part of an ongoing surge in quantum stocks, with D-Wave’s stock price almost tripling over the past year and Rigetti Computing and Quantum Computing seeing share values more than quadruple in that time.

Is It Legit?

Behind these multibillion-dollar market movements lies another, more troubling trend. Loud declarations of various types of quantum advantage aren’t new: Google notably made the first such claim in 2019, and IBM made another in 2023, for example. But these announcements and others were ultimately refuted by outside researchers who used clever classical computing techniques to achieve similar performance. In D-Wave’s case, some of the refutations came even before the Science paper’s publication, as other teams responded to a preliminary report of the work that appeared on the preprint server arXiv.org in March 2024. One preprint study, submitted to arXiv.org on March 7, demonstrated similar calculations using just two hours of processing time on an ordinary laptop. A second preprint study from a different team, submitted on March 11, showed how a calculation that D-Wave’s paper purported would require centuries of supercomputing time could be accomplished in just a few days with far less computational resources.

In response, D-Wave’s King told New Scientist that while such classical feats are “a huge advance,” they were too rushed and incomplete to refute the company’s claims of quantum advantage. “They didn’t do all the problems that we did,” he said. “They didn’t do all the sizes we did, they didn’t do all the observables we did, and they didn’t do all the simulation tests we did.”

Why This Matters

Achieving a genuine and practical quantum advantage has enormous implications, from designing better pharmaceuticals and electronics to overturning the encryption schemes upon which national defense and the global financial system depend. It’s something so disruptive that it could confer almost incalculable wealth and power to whoever does it first—so naturally the competition is fierce.

Critics say, however, that this high-stakes struggle is leading to improprieties in the scientific process and an uneven playing field in the peer-reviewed literature. Simply put, even though the science itself may be sound, the market-driven temptation to overhype results is almost irresistible—with potentially disastrous results for the health of the field if or when confusing disputes over claims cause financial bubbles from qubit-enamored investors to finally pop. “This model of using high-profile publications to broadcast scientific work done within a private quantum company is becoming more and more problematic,” says Giuseppe Carleo, a computational physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), who co-authored the March 11 preprint that challenged D-Wave’s results with his EPFL student Linda Mauron.

The Cycle of Quantum Hype

Carleo says that it’s been a general impression in the quantum-computing community that some major journals encourage bombastic claims from prominent corporate-backed research groups by offering them a friendlier and faster peer-review process. Most media outlets then vigorously cover these supposed breakthroughs but often dedicate slim-to-no coverage to their subsequent invalidation. “This is possibly even more problematic because it fuels quantum hype,” he says. “These journals do not give the same visibility to the scientific voices who are in disagreement with this way of doing science.” Of the multiple recent refutations of quantum advantage claims, Carleo adds, “none have landed a publication in Nature or a journal of similar stature…. And it will also be the case this time with the D-Wave experiment.” (Nature and Scientific American are both part of Springer Nature.)

Even so, Carleo says, there’s nothing wrong with the results from D-Wave, Google, IBM and others, all of which “represent potentially good advances in computational physics.” Rather the problem is the clamor to prematurely declare quantum advantage. “Claims of beating ‘all classical methods’ are very hard to justify scientifically,” he says, “because it’s humanly impossible to run all state-of-the-art classical methods on a given problem to show they’re truly inadequate compared to some quantum method.”

Can the cycle of quantum hype be broken? Doing so will take the combined efforts and ethics of scientists, publishers, journalists and investors—and that’s a problem that may be even harder than wrangling qubits.