Amid a nationwide housing shortage, a new report shows the number of those burdened by rental affordability has hit a record high.

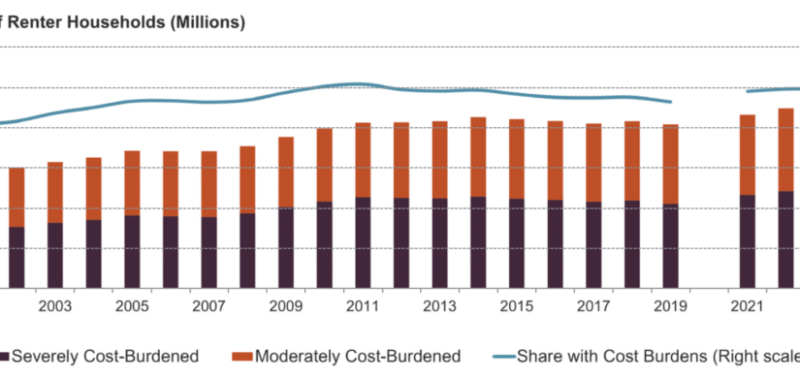

As of 2023, 22.6 million renter households spent more than 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities, up by 2.2 million since 2019. More than half, or 12.1 million, of those spent more than 50 percent of their income on housing costs, according to recent research by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard.

Worsening affordability affects renters across income groups. Middle-income renters, who earn $30,000-$75,000, comprised 41 percent of all cost burdened households in 2023. Those earning $75,000 and more were 9 percent. A full-time job is no guarantee that housing will be affordable. Indeed, 36 percent of fully employed renters were cost-burdened in 2023.

In this edited conversation, Chris Herbert, the center’s director, explains why renting continues to grow less affordable and what cities can try to do about it.

The number of households struggling with housing costs is at an historic high. What’s driving this?

There’s two things. Since 2021, we saw rents going up at double-digit rates in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. In 2023, they started to slow down. In 2024, they were growing at more like an inflationary clip, so “better.” That was a function of very strong demand from the pandemic. Supply couldn’t keep up and led to high rents.

It came on the backs of what had been deteriorating affordability for the last two decades. There was a quiet affordability crisis growing, which is, how many renters were cost-burdened.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, we reached a peak around 2011 in terms of both numbers and share of renters who were cost-burdened. From there, things gradually got a bit better.

But underneath the surface, while the overall share of renters who were cost-burdened was edging down, the share of renters working year-round, full-time, at not great but not terrible jobs, we were seeing a sharp increase in the share of renters who were cost-burdened.

What was happening was the cost-burdened/housing affordability issue was really being democratized. It was spreading from just among the poorest households to more working folks, particularly young people.

There was a real worsening of the crisis since the pandemic, but it had already been getting worse, and particularly worse for working people.

The number of cost-burdened renters has hit another record high

Many more middle- and higher-income renters are struggling with housing costs. What accounts for that shift?

That’s kind of the $64,000 question. The most common answer people give is that we haven’t been building enough housing. To some extent, that’s true. Multifamily vacancy rates had gotten quite tight, particularly in the face of the pandemic surge. So, there was a sense that we didn’t have enough apartments.

That is a piece of the story, but we almost overemphasize it. The other part of the story is that the cost of producing housing units is very high. There’s this notion, “Build more houses, and the price will come down.” You have to bear in mind that builders only build housing if it makes economic sense to do so.

The expense comes in four big buckets: There’s land, and that’s where a lot of the conversation has been around zoning and the fact that we don’t have enough land zoned for high-density housing. And then there’s construction costs — that’s 60 percent of the cost of an apartment building. The land, typically, is only 20 percent. And then there’s the soft costs: architectural, engineering, and then, financing. Those costs go up with a difficult approval process. They’re about 10-15 percent of the cost, so not a big driver. But the financing costs, when interest rates go up to 7 percent, is a big driver.

Housing is expensive for a host of reasons, zoning being one of them, construction costs, and the fact we haven’t had improvements in efficiency in the construction sector, and then the complexity of the approvals process and the high cost of capital.

Boston mayoral candidates Josh Kraft and Mayor Michelle Wu said housing affordability will be a top issue in the upcoming election. Do mayors and cities have any real tools to bring down housing costs?

There’s been a lot of discussion and emphasis on the regulatory processes. How restrictive is your zoning? How onerous is your approval process? How hard is it for a developer to propose a reasonable scale development and get it approved and start work on it? A big thing cities are doing is relooking at their zoning. Cambridge has done various iterations of looking at their zoning.

Related to that can be the approval process: The affordable housing overlay in Cambridge says if you put forth a development that meets criteria in terms of setbacks and density and other factors, we’re going to approve it, and you don’t have to go through a whole process of design review. So, cities can do that.

How does that affect affordability? It reduces the soft costs. To the extent you’re giving me greater density, I may be able to get a better value of land. The challenge is that the land’s value is based on how many units you can put on it. And so, if you tell me I can put two units on it, and the land was worth, say, a million bucks, and then you say, “Now you can put 10 units on it.” That’s $100,000 a unit. I just saved a ton of money.

But as soon as you tell a developer you can put 10 units on it, the developer says, “I’ll pay 5 million bucks for that piece of land.” So, you don’t get as much savings from the density. All cities can do in that regard is try to make it so there’s not more friction and more pressure on prices to go up faster than they otherwise would.

You’re going to have a hard time solving the affordability problem through zoning. And if you’re talking about lower-income households or even moderate-income households, you’re going to have to talk about ways in which you’re going to subsidize the cost of that housing. That means cities have to find ways to get money.

Boston has been very good about linkage payments for commercial development generating a fair amount of money, as has Cambridge, and an affordable housing trust that gets money from that. They can use some general appropriations from their budget.

You can also look for special taxes. Boston put forward a transfer tax proposal that former Mayor Marty Walsh estimated would generate about $100 million a year in income for the Affordable Housing Trust. Mayor Wu pursued it, but the state legislature has stymied them.

A big issue for cities is how do we get more financial resources to help subsidize housing. One of the things cities can do is go catalog all the land they own. That land can be an important subsidy. Boston’s been doing that.

“A big issue for cities is how do we get more financial resources to help subsidize housing. One of the things cities can do is go catalog all the land they own. That land can be an important subsidy. Boston’s been doing that.”

Chris Herbert

And maybe spur innovation in the design of housing. Boston’s Housing Innovation Lab has been looking at how do we get more modular housing, more efficiencies of factory production and how can the City of Boston play a role in trying to help that get to scale.

Any promising policy ideas or positive trends on the horizon?

We’re definitely in a situation where we have to try a lot of things. There’s a lot of experimentation. There’s a piece in the Mass. state bond bill for a revolving loan fund. People have come to the realization that housing affordability has been a long-term problem that’s been a long time in the making, and so we have to have a long-term vision of how we address this.

One of the big ways in which housing inflates in value is through the inflation of land values. Houses depreciate, and so, the value of a house built in 2000 should be less today. But in fact, housing values around here are double what they were in 2000, and that’s all in the land value. It’s land values that capture a lot of the inflation in house prices. And so, one thing to do is to lock in land ownership long term to keep that inflation from affecting the occupants of the home.

The other piece is that if [property owners] manage housing at cost then you can start charging rents that are a lot more affordable. Combine that with public ownership or nonprofit ownership that could be exempt or limited property taxes, low-cost land, at-cost rents, and reduced costs from reduced property taxes, you can start to get housing that is affordable.

Source link