It’s Monday, Oct. 25, 1999, and caddy Mike Hicks is on the ground at the Champions Golf Club in Houston, Texas, preparing for the 1999 Tour Championship. Tiger Woods had just won the National Car Rental Golf Classic Disney the day before in Orlando, while Hicks’ man, Payne Stewart, missed the cut.

That allowed Hicks to get to Houston sooner than expected, so he could walk the course, figure out sightlines, and make notes for Stewart, who would play later that week. Like the current edition of the Tour Championship, only 30 players teed it up then. But instead of the FedEx Cup rankings, the season-long money list determined the field until 2006. Thanks in part to his U.S. Open triumph at Pinehurst No. 2 earlier that year, Stewart sat in third on the money list, behind only Woods and David Duval. The 42-year-old was one of the best players in the world.

So early that morning, Hicks went about his normal routine, getting ready for the big tournament to come. He had scouted eight holes already, and while on the 9th fairway, Hicks heard his cell phone ring. It was Dan Swiniarski, the Director of Golf at Hicks’ home club back in North Carolina.

“Hey man,” Swiniarski said to Hicks over the phone.

“There’s something going on with a PGA Tour player, and they think it’s Payne Stewart.”

“What’s going on?” Hicks asked.

“Yeah, man. You need to get to a TV. It’s on CNN,” Swiniarski replied.

An overwhelming sense of dread descended upon Stewart’s long-time looper. He didn’t know what was wrong, so he quickly hung up the phone and started to make his way back to his hotel room. But before he could even figure out which direction to go, his phone rang again.

It was Tracey Stewart, Payne’s wife.

She delivered the harrowing news to Hicks that Payne’s plane, scheduled to fly from Orlando to Dallas that morning, had lost air pressure within the cabin. Air traffic controllers had lost contact with the pilots in the sky, and the plane was flying in a northwesterly direction without control. In addition to Stewart, his agent, Robert Fraley, and four others were on board, including the two pilots.

Stewart planned to stop at his alma mater, Southern Methodist University in Dallas, to discuss the golf program’s future before heading to Houston that night. But he never made it.

Hicks eventually did make it back to his hotel room and watched everything unfold on the TV. He could not believe his eyes. He sat in disbelief alongside his good friend Mike “Fluff” Cowan, who arrived that morning from Orlando. Fluff was caddying for Woods at the time.

Hours later, and still in a state of shock, Hicks flew back home to North Carolina to pick up his wife. They then headed straight for Orlando to be with the Stewart family.

“Tough memories there, bro,” Hicks lamented on a recent phone call with SB Nation.

“Tough memories.”

Mike Hicks got his first big break caddying on the PGA Tour in 1984, when Curtis Strange hired him as a part-time looper. Before then, Hicks, who left NC State in 1980 to pursue a career caddying, had brief stints carrying the bags of David Edwards, Don Pooley, and Lon Hinkle. But he could not turn down the opportunity to work for Strange, even though it was part-time.

In those days, many caddies would split the job, meaning someone would work half the weeks while somebody else carried during the others. With Strange, Hicks split his time with Donnie Wanstall, who also caddied for Hale Irwin at the time. But it was during this period in which Hicks began to develop a relationship with Payne Stewart. As the PGA Tour has done for decades, top golfers play alongside one another from week to week. Marquee or featured groups are nothing new. With Strange and Stewart being top-20 players in the world throughout the 1980s, these two played a lot of golf together, meaning their caddies spent a ton of time with each other, too.

Fast forward to 1987, and Strange, Stewart, and a handful of Americans, including Mark Calcavecchia and Tom Kite, were in Japan for the World Championship of Golf. This Ryder Cup-like event featured players from the U.S., Europe, Japan, and Australasia. Players received an appearance fee if they showed up and a guarantee of $100,000 if they won. Yet, Stewart arrived in the Far East with a new caddy. He recently fired his old looper, Rob Kay, and brought Tim Davies of Jacksonville, Florida, to carry his bag that week.

“I don’t know how [Stewart] found this guy,” Hicks said.

“Anyway, the first day in Japan, Tim Davies shows up and he’s wearing knickers, a Hogan hat, socks, the whole nine yards. And we’re looking at this guy going, ‘Huh?’ I know it threw Payne for a loop, too. He wasn’t expecting it. So, I kind of figured that this wasn’t gonna work out too well.”

At one point that week, Hicks pulled Stewart aside and said, “Look, if this job opens up again, I would like a shot.” As great as Strange was—and he would go on to win the next two U.S. Opens at Brookline and Oak Hill—Hicks wanted to carry a bag full-time for one player. So, a few months later, at the beginning of the 1988 season, Stewart tabbed Hicks for a four-week trial run for the West Coast swing. The newly-minted duo posted four top 10s, all of which could have turned into wins if not for a bad break here or there, but it was still a successful debut for Hicks.

“The rest is history,” Hicks jokes.

Two weeks after officially hiring Hicks as his full-time caddy, Stewart went to Hicks’ home state of North Carolina to meet Dr. Dick Coop, a sports psychologist at the state’s flagship University in Chapel Hill. Conveniently, Hicks resided in nearby Hillsborough at the time, only about 10 miles from the University.

Stewart was already a world-class player. He did everything right. He could shape any shot required. Hole any putt when needed. And he could beat any other player in the world head-to-head. He was not the longest off the tee, but he still managed to contend in every tournament he played. But he lacked one major thing that almost every professional golfer has: a pre-shot routine.

Coop helped him build one as the two would work at Hope Valley Country Club in Durham, with Hicks watching intently.

“I was there listening to everything, and I could reiterate it to him on the course and on the road,” Hicks said.

“If it hadn’t been for Dick and Payne acknowledging the fact that he needed some help mentally, he would have never become the player he did.”

At that point, while on the course and in competition, Stewart focused too much on the problems right in front of him: water, bunkers, out-of-bounds stakes, or whatever hazard threatened to derail a round. As any golfer knows, those penalty areas always manipulate the mind, diminishing a player’s confidence in the process. This mindset often leads to a bigger number and, in turn, missed opportunities.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25697887/81455494.jpg)

So, Coop decided that he and Stewart would focus on the pre-shot routine, which involved establishing an intermediate target. Whether it was a divot, a leaf, or a speck on the turf, Stewart would align his clubface with that spot every time. But before he had a club in his hands, Stewart would first pull on his glove, ensuring it felt tight on his left hand. Then, after his playing partner hit their shot, Hicks would give Stewart his bag, who then would draw a club. Whenever his playing partner’s ball finally came to rest, it signaled the start of Stewart’s internal clock—the point at which he started his routine.

“He was always self-confident. He believed in himself from day one. You don’t get to that level and not believe in what you’re doing,” Hicks said.

“He just needed a little bit to get him over the hump, and he got that from Dick. And then, of course, he won two majors not too far after that.”

Stewart’s first major triumph came at the 1989 PGA Championship at Kemper Lakes in Illinois, where he faced a five-shot deficit going into the back-nine. To give you a sense of where his confidence was, Stewart, on the 10th tee, said to ABC Sports Announcer Jerry Pate, “I’m gonna shoot 30 this side and win the tournament.”

He wound up shooting a 5-under 31, and with some help from Mike Reid, who dropped three shots on the final three holes, Stewart won by one.

His 1991 U.S. Open victory did not come as easily.

Stewart labored through back pain all week yet still managed to sit atop the leaderboard after each round. Nobody loved the U.S. Open more than Stewart, an American patriot of unfathomable proportions. It’s why he loved his national Open and the Ryder Cup more than anything. But after 72 holes at Hazeltine, Stewart sat in a tie with Scott Simpson, forcing an 18-hole playoff the following day.

During that round, a round which Hicks described as “out of control,” Stewart fired a 3-over 75 while Simpson could only muster a 5-over 77. Yet, like his maiden major triumph two years prior, Stewart’s opponent held the lead late and coughed it up. Simpson led by two on the 16th tee, but three costly bogies on the final three holes sealed his fate, thus handing Stewart his first U.S. Open title.

He would go on to contend again in 1992, but a final-round 85—during “hurricane-like” conditions at Pebble Beach—derailed his chances. He was right there again in 1993 at Baltusrol, but Lee Janzen made three birdies over the final five holes to best Stewart by two.

Then, in 1994, Stewart signed an equipment deal with TopFlite, which brought about a healthy dose of struggles. His ball would go straight up in the air without rhyme or reason. Stewart had no control over his golf ball, which explains why he did not record a top-10 in a major until the summer of 1998, when he fell short of Janzen again at the U.S. Open at The Olympic Club.

But that runner-up finish in San Francisco served as a harbinger of things to come for two reasons: one physical and one mental.

First, Stewart made a bogey late in the final round at The Olympic Club after his ball landed in a sand-filled divot. Anyone who has played the game knows this unlucky break leads to unpredictable outcomes. You never know how the ball will react, especially under major championship pressure. So it’s no wonder Stewart spent so much time practicing shots out of sand-filled divots the following year, during the week leading up to the 1999 U.S. Open. He knew that breaks like this could happen.

Yet, perhaps more importantly, Stewart believed in himself again. He knew he could get the job done. Hicks felt that way, too.

“We knew we could still win one of these things,” Hicks recalled.

“I mean, he’s 41 now, but you know what everybody says, ‘Once you get to 40, it’s true, everything starts to hurt. You’re at the top of the mountain, and now, you’re hitting the other side. The body starts aching a little more. But he proved to himself that week, and to me, that, ‘Hey, you know what? He can still do this.’ There wasn’t a question that he can still do this.”

Well, hints of doubt lingered the week before the 1999 U.S. Open. Stewart missed the cut in Memphis, primarily due to a 2-over 73 that he carded in the first round. But his head was not in Southwestern Tennessee. His mind was elsewhere, about 600 miles due east, in the small village of Pinehurst, North Carolina, which was preparing to host the U.S. Open for the first time.

So after his 2-under 69 in the second round, Stewart and Hicks each went home. Stewart would fly up to Pinehurst the following morning, a Saturday. But before he even landed, Hicks had already made the 90-minute drive from Hillsborough to scout No. 2 and was on his way back home when Stewart touched down.

Stewart never carried a yardage book, but that changed this particular week. He spent that Saturday walking the course with his coach, Chuck Cook, bringing only his wedge, putter, and a yardage book. He plotted where he could not miss, taking a red Sharpie and circling the areas around the greens that were absolute no-go’s. Stewart found only one of those spots during the entirety of the tournament. That moment came early during the final round on the 2nd hole, and Stewart holed a six-footer to save bogey.

But a week before that pivotal moment, two important conversations took place on the Sunday before the official practice rounds began.

The first came in the Pinehurst clubhouse.

“I’m sitting there, and we’re getting ready to walk out to the range, and Payne says, ‘Hey, you know what? You didn’t do a very good job last week,’” Hicks said.

“And I said, ‘Yeah, you know, I know I wasn’t as talkative as I normally am. But you know what? I was thinking about this week, buddy. I’m sorry.’”

Stewart understood, but only partially.

“Yeah, me too,” Stewart replied.

“But that’s still no excuse. You did a bad job last week.”

About an hour later, Stewart, Hicks, Cook, and Coop were out on the golf course, walking down the 2nd hole during their first practice round.

Hicks had noticed that Stewart had shied away from an essential part of his pre-shot routine: establishing an intermediary target before his stroke. The results showed something was off, too. Before missing the cut at the FedEx St. Jude Classic, Stewart tied for 24th at the Memorial, missed the cut in New Orleans, and then tied for 60th at the Shell Houston Open, indicating that he arrived in North Carolina with poor form.

So on that 2nd hole, after Stewart played his tee shot, Hicks and Coop walked slowly behind the others, setting up another all-important interaction.

“What’s going on,” Coop said to Hicks.

“Well, for one thing, he’s not picking his intermediate out,” Hicks replied.

On the very next tee box, Stewart stood over the ball with a 3-iron in hand.

“Where’s your intermediate target?” Coop blurted out.

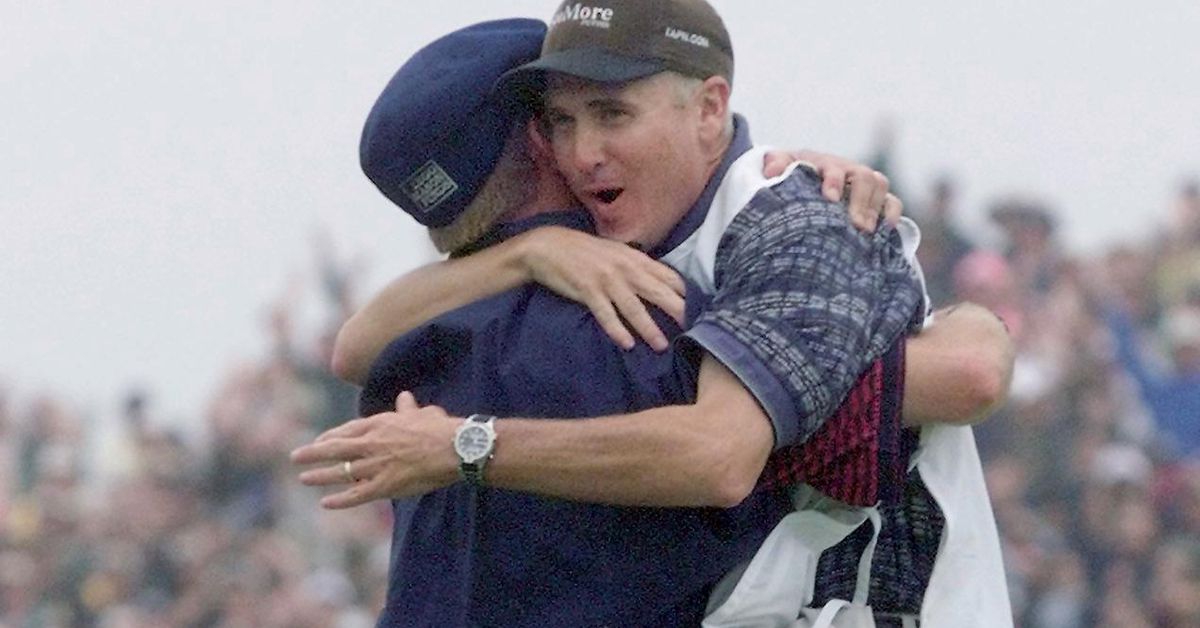

Stewart looked up, pondered, and paused. He then took a deep breath, established his intermediate target, and returned to his old routine. From that point forward, Stewart picked out his intermediate target in both practice rounds and in competition. And, of course, he went on to win the tournament, holing a 20-footer for par on the 18th green to beat Phil Mickelson by one. It has since become one of the most enduring spectacles in golfing history.

“He didn’t want to hear that from me,” Hicks says with a laugh.

“It would have probably gone in one ear and out the other, but when his psychologist—you know, I didn’t tell him that I told Dick, he thought Dick had picked up on it, right? But I’m still convinced we won that tournament because he got back into what he was supposed to do. His pre-shot routine was there.”

But something special was there, too, in the form of a strong friendship. The bond between Hicks and Stewart was unrivaled among other players and caddies. You can still feel it all these years later. The two friends spent so much time together off the course, and their families did, too. So it comes as no surprise that Hicks did not pick up a permanent bag after Stewart’s passing. He rotated among tour players, ranging from Bob Estes to Steve Stricker, but nobody compared to Stewart—through no fault of their own.

Nowadays, Hicks resides in Tennessee with his wife and takes after his aging father. But as Stewart did—and his family continues to do through the Payne Stewart Kids Golf Foundation—Hicks gives back to the golfing world, too. He does so through the Tour Caddy Collective, a group of PGA Tour caddies who serve as motivational speakers at events but, more importantly, teach up-and-comers about what it takes to be a professional looper. Hicks and a few other prominent caddies will host a Professional Caddie Certification program at NC State next February, which will help foster the next generation of caddies in the game. He wants to see more youngsters caddy, and the demand for them far outweighs the supply. But who knows? Maybe, if you do end up caddying, then you will be able to tell stories like Hicks has done for so many years.

Amid the bad memories that linger from this day 25 years ago, those close to Stewart can always recall the countless stories that made him the legendary figure he still is. He was gregarious, charming, and, yes, flamboyant. But he was also beloved by so many, and so many continue to love him to this day.

“Put it this way, the Lord broke the mold when he made Payne Stewart,” Hicks said.

“There’s never going to be another Payne Stewart on this Earth. I can tell you that.”

But what if I told you he’s patiently waiting for your arrival in heaven?

Jack Milko is a golf staff writer for SB Nation’s Playing Through. Be sure to check out @_PlayingThrough for more golf coverage. You can follow him on Twitter @jack_milko as well.