Two figures, a man and a woman, stand at a shoreline. They face away from the viewer and toward the sea, side by side and yet isolated from one another.

Sometimes the woman is on the left. Sometimes she’s on the right. Sometimes these figures, and the rocky shore around them, are rendered in careful brushstrokes; other times, perhaps there is a sense of urgency, of haste, of canvas left untouched.

This is “Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones,)” one of the most famous motifs by the Norwegian painter and printmaker Edvard Munch (1863-1944.) Munch returned to this motif again and again over more than 40 years, in paintings, metal-plate etchings, and a series of woodcut prints, each with slight differences in color, shape, or technique.

“He couldn’t let go,” said Elizabeth M. Rudy, Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints at the Harvard Art Museums and the co-curator of the exhibition “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking,” on view through July 27. “There are so many more iterations of [‘Two Human Beings’] … in black and white, in grayscale, all violet, monochromatic but in different color schemes, totally different color combinations. There was one we saw in neon color, and the whole thing became psychedelic. With the intensity of variations, the motif starts to have less and less singularity and it can be a vehicle, an exploration of pretty much anything under the sun.”

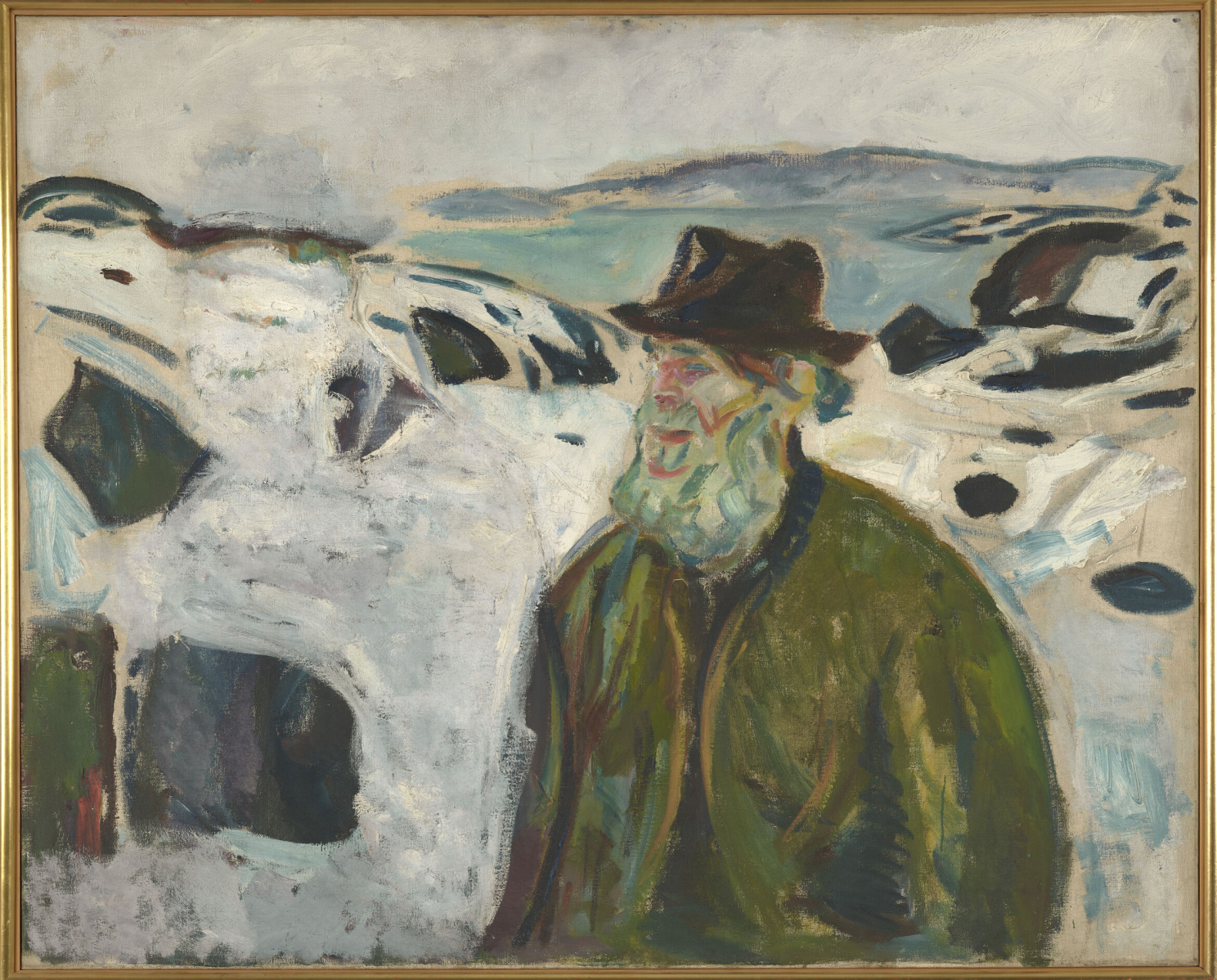

Munch’s repeated returns to the motif demonstrate the way his paintings informed his prints, and vice versa. He first painted it in 1892, but the painting was destroyed in 1901 in an explosion onboard a ship that was transporting his works for exhibition. When he next painted the motif in about 1906-1908 (above left), he had already experimented with woodblock prints of the theme. The figures appear in reverse from the original painting and were thus likely based on the printed versions, which he would have had as a ready reference.

“He’s mixing a huge range of different painting techniques,” said Lynette Roth, Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, co-curator of the exhibition. Munch left some of the canvas unpainted; in some places, he applied paint thickly or scratched color away. It’s more than a demonstration of versatility, Roth said: “It also creates a kind of vibration, a sensation of these figures, a dynamism in the painting itself.”

The final version, made in about 1935 (above right), appears more spontaneous than its predecessor, with exposed lines from Munch’s preparatory sketch, large swatches of color, and areas of exposed canvas.

“It was something we were hoping to highlight,” Roth said. “Why this return? What is he learning over time and through the different techniques?”

The Lonely Ones, together and apart

© Munchmuseet / Richard Jeffries; © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

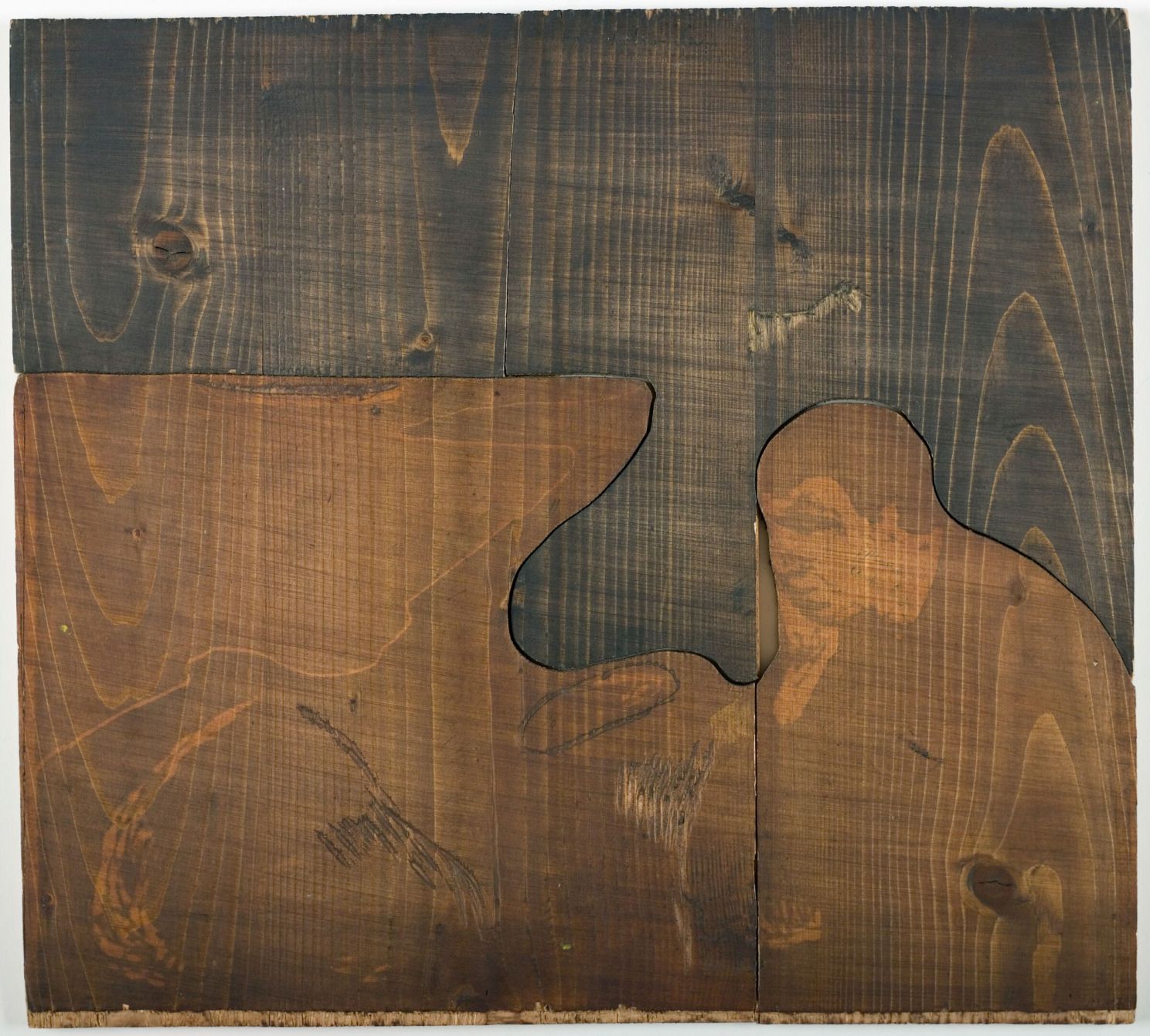

In his prints, Munch exploded “Two Human Beings” and put it back together again. He used a jigsaw method, inscribing his design onto a block of wood and using a fretsaw to cut each element into its own piece. Then, he could ink each piece separately, push them back together, and run the reunited composition through the press, creating endless variations of color.

Munch incorporated the male figure into the landscape but cut the woman into her own solitary block.

“She almost feels like a doll,” Roth said. “You can take her out, as opposed to the man, who becomes a part of the printing of the landscape. In many of the prints, he begins to feel like he’s more a part of the landscape, whereas she is able to be this very singular figure and a very important one for Munch.”

“He embraced the non-perfect alignment, the break in the block that would be seen then in later prints, the fact that in the painting, things are dripping, things are imperfect. That was something he emphasized: That the too-perfect finish was actually the enemy of the good in a work of art.”

Lynette Roth

“Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)” has long been understood as a rumination on isolation, on the sense of loneliness that one can feel even in the company of someone else. But after spending time with Munch’s multiple iterations on the motif, Roth said she’s not so sure that’s the only interpretation.

A savvy businessman, Munch originally titled the work simply “Two Human Beings.” But when others ascribed loneliness to the figures, Munch leaned into it.

“The more I engaged with this, I started to feel like they actually aren’t that lonely,” Roth said. “They’re connected to the landscape; they’re connected also to each other in the way that color unites them, and the way he’s inching toward her. … For me, it’s also companionship and contemplation, which doesn’t have to be devastating or alienating or cause for anxiety.”

A question of finishMunch’s contemporaries sometimes critiqued a lack of polish in his pieces. But Munch embraced the flaws, imperfections, and empty spaces in his work.

In the final painted version of “Two Human Beings,” Munch leaves exposed sketch lines and areas of bare canvas on the woman’s dress.

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings. The Lonely Ones, c. 1935. Oil on canvas. Loan from Munchmuseet, Oslo, TL42724.1. Photo: © Munchmuseet / Ove Kvavik.

Munch painted over a second figure, creating a visible echo of an earlier iteration of “Old Fisherman on Snow-Covered Coast.”

Edvard Munch, Old Fisherman on Snow-Covered Coast, 1910–11. Oil on canvas. Loan from Munchmuseet, Oslo, TL42724.10. Photo: © Munchmuseet / Halvor Bjørngård.

“Inger in a Red Dress” is composed on board, a cheap support that artists often use when creating studies. But the painting is a fully realized portrait.

Edvard Munch, Inger in a Red Dress, 1894. Oil paint, oil pastel, and watercolor on board. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Lynn G. Straus in memory of Philip A. Straus, 2012.258. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

“Berlin Model” may appear unfinished, but the surface is coated in casein, a milk-derived medium that has a paper-like texture when dried.

Edvard Munch, Berlin Model, 1895. Oil on canvas. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Gift of Harry and Patricia Irgens Larsen, 1991.215. Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums.

A gap is visible in the woodblock for “Melancholy I.” Munch was known for allowing imperfections to become part of his compositions.

Edvard Munch, Evening. Melancholy I, 1896. Woodblock (oak). Loan from Munchmuseet, Oslo, TL42724.6. Photo: © Munchmuseet / Richard Jeffries.

A new lens on Munch

Munch has long been understood as a deeply troubled artist whose struggles with mental health are apparent in psychologically evocative works like “The Scream.” But “Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking” invites viewers to disentangle Munch’s artwork from his biography and to view his recurring motifs not only as a window into his psyche but as another material, like paint or charcoal, a vehicle through which Munch explored his artistic practice.

“We know that people will react emotionally or psychologically to what’s on view,” said Peter Murphy, Stefan Engelhorn Curatorial Fellow in the Busch-Reisinger Museum and co-curator of the exhibition. “Two things can be true: Munch did suffer psychologically; although he was wealthy and well-off, he did have a lot of crises in his life. And he was also a mastermind of getting his work out there and exploring it.”

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch was one of the most significant artists of the Modernist movement, and an innovator in printmaking, painting, and other arts. He is best known for his painting “The Scream,” which is seen as an expression of modern spiritual angst. He was active for more than 60 years, from the 1880s until his death.

“Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking” is on display through July 27 in the Special Exhibitions Gallery on Level 3 at the Harvard Art Museums. The exhibition showcases 70 works, primarily from the Harvard Art Museums collection. Thanks to a transformative gift from Philip A. and Lynn G. Straus, the museums now house one of the largest and most significant collections of artwork by Munch in the U.S.

Source link