[ad_1]

Many female designers from the mid-century modern movement are more celebrated now than when they were producing work, says design historian Pat Kirkham in this interview for our mid-century modern series.

US designer Ray Eames, French designer Charlotte Perriand and architect Lina Bo Bardi are some of the women recognised today for their contributions to the mid-century modern movement, which spanned the mid-1940s to early 1970s.

Kirkham, a design history professor at Kingston University who has authored books on designers Charles and Ray Eames and 20th-century female designers in the US, argued that a revived interest in mid-century modernism has brought some of these women’s names to the forefront of design again.

“There are still some architects who don’t see them of value”

She explained that although they gained commercial success with their designs in the decades after world war two, many of the designers faced adversity in the industry.

“There were many routes these women took to becoming what they were, and they didn’t come without sacrifices and frustrations – I think they’re very empowering,” Kirkham told Dezeen.

“The possibility that these women were really good and did some important work is not challenged as much now, but there are still some architects who don’t see them of value, and equally, seeing areas that they hold as women’s work, like interior design, as not as valid as other areas of design.”

According to Kirkham, it was common for women not to be credited for their designs in the mid-twentieth century. These included Ray Eames, who is known for the work she created with her husband Charles Eames.

The Eameses were prominent figures in the mid-century design movement. They met in 1940 at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where Ray had joined as an abstract painter looking to expand her artistic practice and Charles was an architect on an industrial design fellowship.

Ray and Charles married in 1941 and established the Eames Office in Los Angeles. Together, they became influential designers in architecture, furniture, graphic design and film, but Ray was often given less credit than her husband.

Herman Miller furniture sold under Charles Eames’s name

They designed numerous pieces for furniture brand Herman Miller, including the iconic Eames Lounge Chair in 1956.

“Undoubtedly, a lot of stuff went out in Charles’s name,” said Kirkham, “Herman Miller furniture was sold for donkey’s years as ‘by Charles Eames’.”

“Now, Ray seems to almost be as much a household name as Charles Eames used to be.”

Kirkham also said that Ray, who she interviewed before the designer passed away in 1988, had talents outside of her partnership with Charles. These were often overlooked, but are now being discovered posthumously as mid-century modernism and the Eameses’ work continues to inspire.

“You get a very different picture if you focus in from the woman’s angle,” said Kirkham. “Just by researching Ray, there is a ton of stuff nobody had bothered with.”

“Ray’s influence was really strong with interiors – the importance of her to their aesthetic was really crucial.”

“He was quite an arty type of architect, but he was also hugely interested in the technology,” Kirkham continued. “Ray often said that she felt that one of the things wrong with American education when she was young was women weren’t taught technology – she felt it would have been handy for her.”

Perriand is another designer whose designs have been miscredited. Between 1927 and 1937, she collaborated with architects Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret on furniture designs, including the LC2 Grand Confort chair and Chaise Lounge, but as a woman, she was not given as much recognition as her male counterparts.

After 10 years working for Le Corbusier, Perriand “stepped out of his shadow into a successful career of her own,” The New York Times said.

Perriand continued designing into the mid-century and developed a particular interest in creating shelving. One of her most notable designs is the Bibliothèques modular storage system, produced by French architect Jean Prouvé’s eponymous atelier.

Perriand furniture allegedly falsely credited as co-designed with Prouvé

She created further iterations of the shelving under the title Nuage, which were produced by Galerie Steph Simon until 1970.

Perriand’s family later became embroiled in a lengthy legal dispute over the authorship of Nuage, which they allege had been falsely credited in part to Prouvé after his death.

Although her collaborations with male designers had, in some cases, left her overshadowed and miscredited, Kirkham believes her ties to Le Corbusier mean Perriand is now more easily discovered than other female mid-century modern designers.

“In the European modern movement, you often have designers not getting due credit,” said Kirkham.

“With Charlotte Perriand’s designs for Corbusier in the 1930s, she got reclaimed from history because she was working with a really famous architect.”

Extra attention should be focused towards discovering more about the female designers who worked in Central and South America, said Kirkham.

She explained that people’s interest in modernism often leads them to the designs of prolific European and North American men from the movement, but this could be directed elsewhere.

“The interest in modernism is still often what drives most of the interest in the male designers, so my sense is that there is still a tonne of women to be discovered,” she said.

“The work from Central and South America needs much more interest, but the modernism interest comes first.”

Bo Bardi is one of the better-known South American designers of the mid-century. Born in Italy, she moved to Brazil with her husband after a trip to Rio de Janeiro in 1946.

Based in São Paolo, Bo Bardi became a Brazilian citizen in 1951. In the same year, she completed her first built architecture project with her own home, Glass House, and designed the iconic Bardi’s Bowl Chair.

Kirkham named Cuban-born Clara Porset as another designer of particular interest. Porset spent time studying in Paris and the US and although she returned to Cuba, she was forced to leave the country in 1935 because of her involvement in the Cuban general strike.

Finding refuge in Mexico, the country’s culture and vernacular furniture influenced many of her designs, including the wood and woven wicker Butaque chair.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) described Porset as a “design trailblazer” and claimed she was the only woman known to have worked with the most high-profile Mexican modernist architects, including Luis Barragán, Max Cetto, Juan Sordo Madaleno and Mario Pani.

“New names are being uncovered every day”

Kirkham believes it is important to correct the errors of the past that allowed some women’s mid-century modern designs to be overlooked.

With widespread interest in mid-century modernism today, she explained that some people are revisiting old documents and discovering more female designers from the movement.

“One of the interesting things is that mid-century modern was not popular in the 1980s,” said Kirkham. “There is a huge revival of interest at the moment.”

“It’s an important legacy, and new names are being uncovered every day,” she continued. “They’re very empowering, and I think they’re very empowering among young design students.”

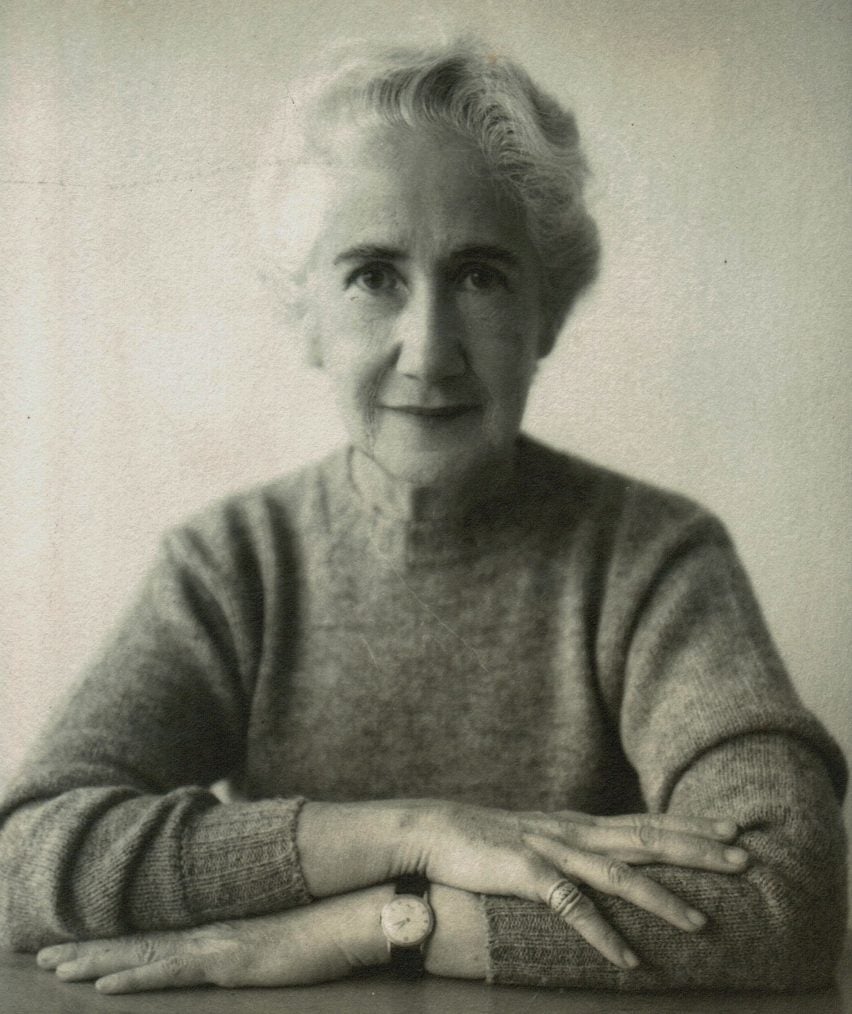

The top photo of Kirkham is by Casey Kelbaugh courtesy of the Bard Graduate Center.

Mid-century modern

This article is part of Dezeen’s mid-century modern design series, which looks at the enduring presence of mid-century modern design, profiles its most iconic architects and designers, and explores how the style is developing in the 21st century.

This series was created in partnership with Made – a UK furniture retailer that aims to bring aspirational design at affordable prices, with a goal to make every home as original as the people inside it. Elevate the everyday with collections that are made to last, available to shop now at made.com.

[ad_2]

Source link